UNSUNG HERO SAVING MUSICIANS FROM THE NAZI HOLOCAUST

One of the most significant conductors of the late 20th century was saved from the gas chambers of Central Europe by the intervention of a Berkeley orchardist. He never got the benevolent attention warranted for his multiple rescues of Budapest musicians in the 1930s.

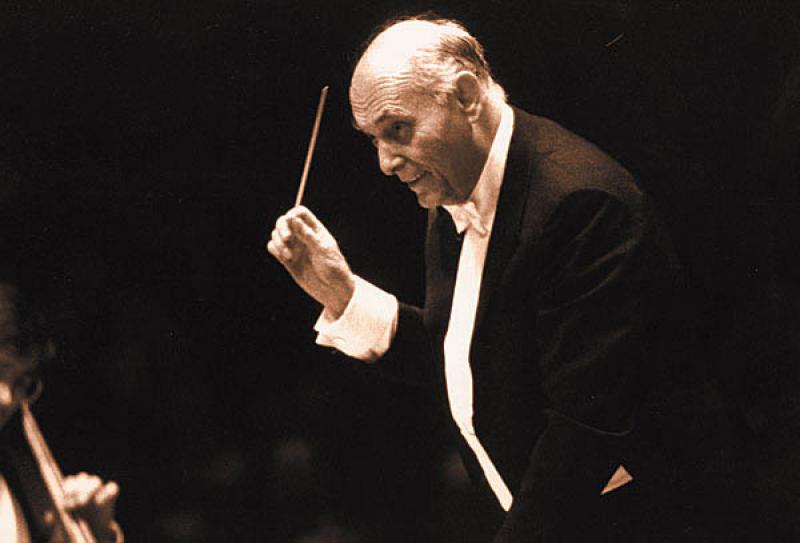

The stellar musician who emerged hale and hearty from the war years was Georg Solti. Repositioned in London, he eventually became a music legend, leading orchestras and opera in performances and recordings and garnering major awards. As conductor, he won 31 Grammy awards, a record that has yet to be surpassed by anyone today.

Enter Alfred Fellner, originally an industrialist and board chairman of the Budapest Opera. Helping emerging musicians, he recognized young Solti’s great talent and realized the need for establishing the latter’s international career as war clouds and mass persecution loomed near the start of World War Two.

A young rehearsal pianist and chorus assistant at the Hungarian opera, Solti was brilliant enough that Fellner financed his career’s start in Austria. As the two had no musical connections abroad, Fellner simply told him to arrive a few days early to the vaunted Salzburg Festival, and make himself known to the administrators. Solti was prepared to spend days there sitting in the offices when the great maestro Arturo Toscanini blew in and thundered that he needed to start choral rehearsals for the opera immediately. Impossible, he was told, as the chorus director hadn’t arrived in town yet.

The crisis was not alleviated till the totally unknown Solti approached and volunteered his services on the spot. Muttering about the ignominy of having to deal with green collaborators, Toscanini recruited him provisionally to start at once.

Solti proved his mettle and was permitted to stay on in various musical assignments throughout the festival before returning home to Budapest, with valuable experience and contacts under his belt.

When Jews were openly attacked by the Nazis and war threats loomed, again Fellner intervened. The vulnerable Solti had to emigrate, as he had Jewish antecedents. A yet more complex agenda meant financing and sending Solti off to Switzerland, where he would both stay safe from the Nazis and bank on his pianistic skill. There Solti won a piano competition, and his safety was secured through the war.

After World War Two he could spread his wings around Europe and get bookings as a conductor of both symphony and opera; his career was made. Solti won rafts of awards and made recordings, including a unique complete Wagner “Ring” cycle on LPs with sopranos Birgit Nilsson, Kirsten Flagstad and other vocal stars. Though an immigrant, he was knighted by the British Crown.

Around 1980 he took his Chicago Symphony on a U.S. tour. For his San Francisco date, the orchestral instruments were stuck in the snow over the High Sierra, and the concert could not begin. He alertly subbed a chamber-music program at Davies Symphony Hall, in his much belated U.S. debut as a pianist—-going back to where he had begun some four decades earlier in Switzerland.

Solti never forgot the immeasurable debt he owed Fellner, who meantime had moved to Berkeley, California, lived just off Claremont Blvd., and managed orchards in the Valley that he had purchased. For every gala opening in London, Fellner was offered complimentary tickets. And with every new Solti recording, a copy was rushed off across the Atlantic to the benefactor. The gratitude was immeasurable.

Back in the late 1970s I asked Fellner if he had helped other musicians escape and avoid annihilation. He smiled, answering, “Quite a few. But Solti was the only one who did not forget.”

By then, the stature of both Alfred Fellner (1897-1981) and Solti (1912-1997) was unassailable. The sad codicil to the story is that Fellner never got his due recognition for opening the padlocked door to escape to freedom for a raft of prominent musicians during the darkest days of the 20th century.

Better now than never.

END