CAN AILEY CO. BUILD UPON ITS PAST?

Its Old Repertory Is Still the Best

By Karl Toepfer

artssf.com, the independent observer of San Francisco Bay Area dance

Weeks starting April 28, 2015

Vol. 17, No. 56

BERKELEY — Last week, the Alvin Ailey Company visited Berkeley, bringing with it three programs in six concerts. The programs mostly featured new works receiving their Bay Area premieres and works adopted by the Ailey Company. The only piece choreographed by Ailey was Revelations, his great, enduring, and immensely popular hit from way back in 1960, which concluded each program. It is indeed remarkable that the Company remains exceptionally vigorous, exciting, and prosperous without having to depend heavily or even much at all on the choreography of its founder, Alvin Ailey, who died in 1989. I saw “Program C” on April 25. Eighteen dancers performed, and it is only rarely that one is able to see modern dance operate with such a large ensemble.

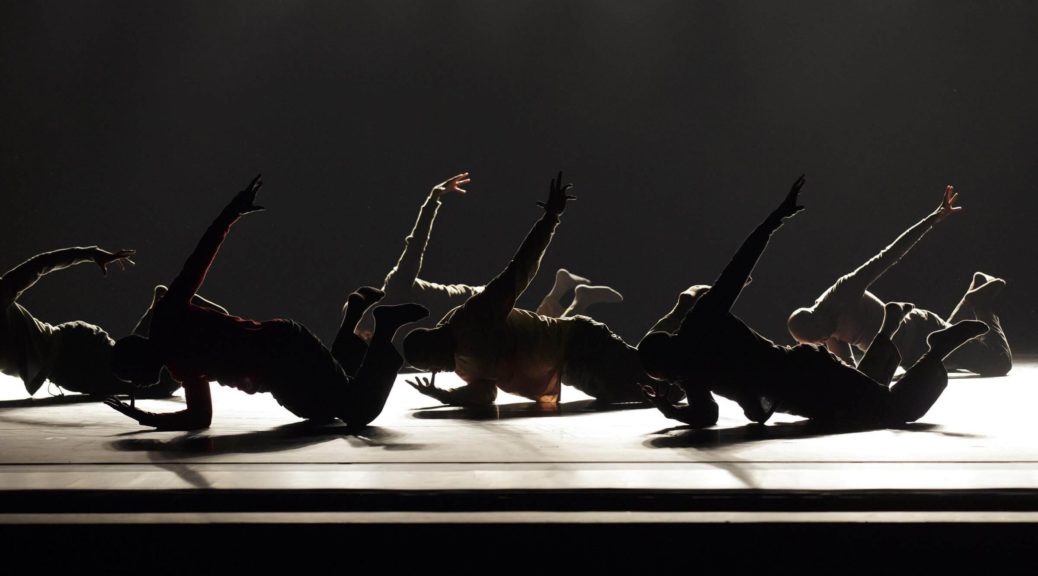

The concert opened with the Ailey premiere of Uprising, choreographed by the Israeli-British dance-theater artist Hofesh Schecter, who introduced the piece through his own company in 2006. Schechter was also responsible for the music, which features a thunderous, pounding ostinato, like the sound of a gigantic stamping machine. The stage is dark, illuminated only by nocturnal sidelights, a spotlight, or an occasional set of strip lights seeking to penetrate the fog that veils the empty, vaguely industrial scene. The piece presents seven men dressed in pants and pullover shirts, facing the audience in a line, but the apparent unity disappears, as the group disintegrates into pairs and a kind of frantic muscularity. The men can’t seem to find a movement that provides them with a sustained sense of unity. They gather in circles or huddles, but they can’t overcome fundamental differences: a pat on the shoulder turns into a hostile punch; jocularity turns into thuggishness. Bonding and fighting are inextricable. A great deal of very rapid, athletic scrambling, jostling, and buzzing around ensues. Some of the movements are quite interesting, such as a sort of crawling-hopping like a wounded chimpanzee, a waddle-shimmy, and a zombie-like procession accompanied by the sound of heavy rainfall. The piece is a bit too long, but eventually the men are able to form a coherent group and raise one of their members up before the audience holding a little red flag, although it was not clear to me what movements or actions or conditions actually precipitated this unified feeling of “rising up” other than some cryptic, mutual recognition that they are all victims of the dark, oppressive environment.

The second piece favored the female dancers of the Company. Suspended Women is a 2000 piece adopted by the Ailey Company in 2014. The choreography is by Jacqulyn Buglisi, a veteran of Martha Graham’s company, and the music is by Maurice Ravel, chiefly the Piano Concerto in G. The piece exudes an early twentieth century atmosphere, but the stage still remains rather dark. Eleven women glide forward in a line; they wear ballroom dresses. They dance together, gracefully, with swirling, undulating, pivoting, and darting movements, but they don’t really dance with each other. It is a group without any fundamental tensions or conflicts or impulses to reorganize or abandon the melancholy lyricism that creates the group. The appearance of four men disrupts the romantic reverie of the women. The men divide the women, they slip between the women, partner them, trade them with each other, hoist them, lay them low, and in general guide them away from moving in the exclusive world that began the piece. But the women somehow manage through their graceful response to every situation to reassemble their group and recover the exclusive elegance and self-contained, refined melancholy with which they began the piece. Suspended Women is a very pretty work, suffused with an overpowering feminine desire to please through lilting gracefulness. It is the opposite of Uprising, with its determination to impress with overpowering muscular masculinity.

After the Rain Pas de Deux is another 2014 Ailey Company adoption; the original choreography was in 2005 by Christopher Wheeldon, with music by Arvo Pärt. The piece involves only two dancers (Akua Noni and Jamar Roberts) and describes the complex relationship between a male-female couple. The pair make use of the entire stage, making the point that their feelings for each take up a lot of space. Much of the dance consists of movements involving physical contact between the man and the woman, as they sidle up to each other, cling to each other, coil themselves around each other, slip over, under, and around each other, cradle each other, push each other, encircle each other, and inflame each other. What makes the piece compelling and unlike a conventional pas deux is that the couple use their bodies to build a little architecture of their relationship. The dancers make their bodies form physical structures that support each other, so that the conjoined bodies appear like little buildings, like little towers or even ramparts. And this architecture metamorphoses, as one structure seems to fold or flip into another. But like more conventional pas de deux, the piece includes a couple of spectacular lifts of the female body.

The program concluded with perhaps Alvin Ailey’s most famous work, Revelations, which involved the entire Company ensemble. The piece uses ten African American spirituals as musical accompaniment, and the dancers wear costumes that evoke sometimes the rural South, sometimes a Caribbean milieu, and sometimes an urban environment from a time before we were born. The dances are at moments mournful or lamentational and at other moments boisterous or exultant. The piece is 55 years old, yet it hardly seems to have aged. It is as “modern” as the twenty-first century pieces elsewhere on the program, and it delivers much more emotional intensity and variety than the other pieces. Seeing Revelations makes one see how conservative modern dance choreography has become in our time and how hesitant it is to engage with large and complex emotional conditions. The audience, however, was quite thrilled with the concert and gave it a standing ovation. The ensemble responded with an encore reprise of a scene from Revelations.

A large ensemble of beautiful male and female bodies moving beautifully and always barefoot is a wonderful thing to behold, but it does exact a cost. The scenic environment is minimalistic, reduced almost entirely to modest lighting effects on a bare stage. Costumes are consistently “appropriate” without being very interesting. Except for a parasol in one of the Revelations scenes, props are non-existent. The dancers execute their movements with great conviction, energy, and refinement. They are marvelous talents, capable of substituting for each other on different performances; they produce a powerful image of group cohesion. At the same time, however, the concert conveyed the impression that modern dance remains only as modern as it was in 1960. The Company’s repertoire may now consist largely of works created after Ailey’s death, but these works do not seem to embody a conception of dance or movement or scenic context that is any more modern than what Alvin Ailey made so astonishing when he started the Company in 1958.

The Alvin Ailey Company performs at Zellerbach Hall through April 26, then travels to Baltimore with the same concert series starting May 1.

#

© Karl Toepfer 2015

Karl Toepfer is a dance reviewer for artssf.com.

These critiques appearing weekly (or sometimes semi-weekly, but never weakly)focus on theater, dance and new musical creativity in performance, with forays into recordings by local artists, and a few departures into books (by authors of the region)as well.

#